What Makes a Good Scenic Design Rendering?

Lessons from Fine Art for Theatre, Theme Parks, and Live Experience DesignIntroduction: Why Scenic Renderings Matter

In scenic design for theatre, theme parks, and live entertainment, a rendering isn’t the final product—it’s a bridge between idea and emotion. It's a visual story that helps collaborators, clients, and audiences believe in a world that hasn't been built yet.

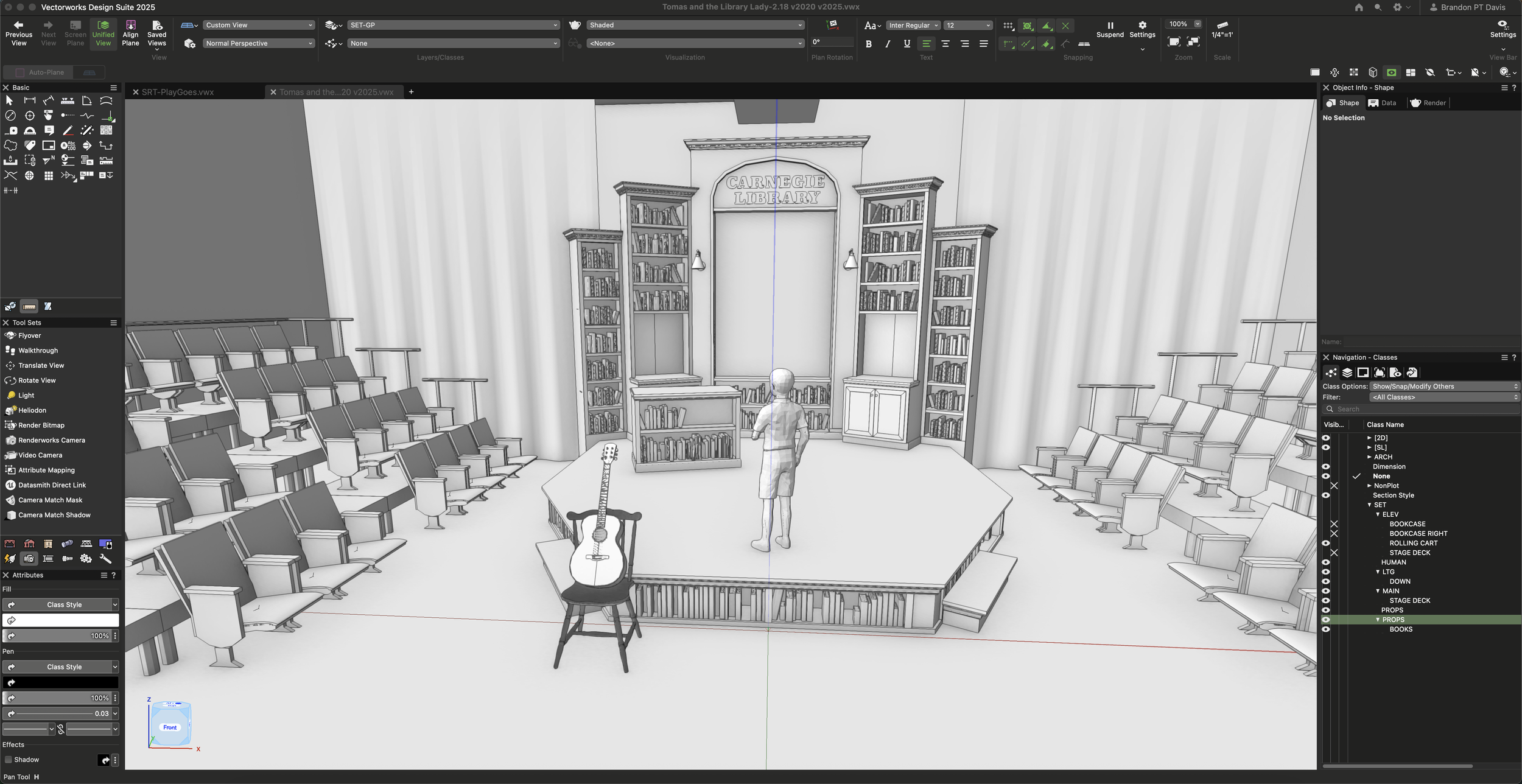

Before we get into lighting styles or textures, let’s talk about the software that supports this work: Vectorworks.

Vectorworks: A Tool for Storytelling and Precision

Vectorworks serves a dual purpose: it's a drafting/documentation tool and a 3D rendering engine. Its strength lies in accuracy—you can build from the plan up with real-world scale and dimensional clarity. That precision makes it ideal for scenic design, where collaboration with technical directors and production teams is constant.

Unlike mesh-heavy software, Vectorworks models stay clean, geometric, and readable, especially for beginners. While it isn’t optimized for organic modeling, it creates a solid foundation for scenic work that needs to communicate both art and feasibility.

I use Vectorworks because it keeps the technical side as strong as the artistic side—and that balance matters.

Vectorworks rendering in progress. Drafting and visualization happen in the same space.

Lessons from Fine Art: Rendering as Visual Storytelling

To teach what makes a rendering successful, I often turn not to software—but to painting. In a recent lecture, I led students through examples by Caravaggio, De La Tour, Rembrandt, and Hopper. These artists didn’t just paint spaces. They crafted moments.

Their tools were oil and canvas. Ours are digital. But the goals are identical: guide the eye, evoke emotion, and give clarity.

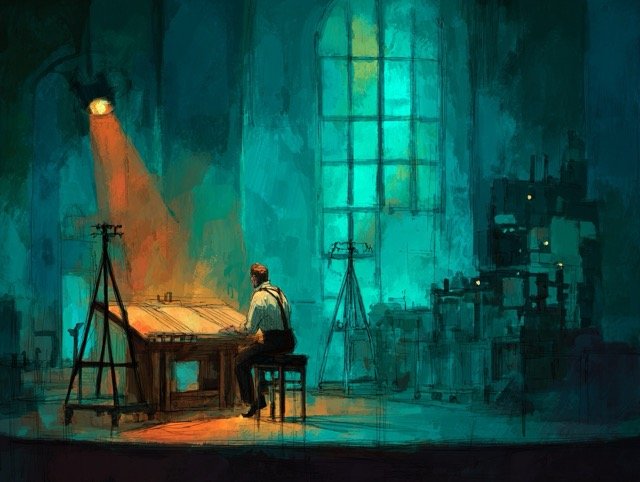

Georges de La Tour – The Penitent Magdalene

Focus: Atmospheric Lighting

Takeaway: A single light source creates emotional tone and spatial clarity.

Rendering Insight: Less is often more. Lighting should support story, not just visibility.

Caravaggio – The Calling of Saint Matthew

Focus: Focal Point & Composition

Takeaway: Diagonals, light direction, and body placement tell the whole story.

Rendering Insight: Stage your scene. Guide the eye intentionally.

Rembrandt – The Night Watch

Focus: Visual Hierarchy

Takeaway: Use light to highlight important figures, and shadow to let others recede.

Rendering Insight: Complex spaces still need clarity. Prioritize depth.

Edward Hopper – Nighthawks

Focus: Architectural Framing & Mood

Takeaway: Emotion comes from silence, spacing, and negative space.

Rendering Insight: What’s outside the rendering matters too. Suggest a world beyond the walls.

The Core Elements of a Good Scenic Rendering

1. Story Comes First

A rendering without story is just a diagram. Before it sells a space, it should feel like a moment. Whether it's tension, warmth, anticipation, or emptiness, your rendering should communicate something even if the viewer doesn’t know the play, script, or event yet.

If your image doesn’t evoke an emotional cue, then no amount of detail will matter.

2. Human Figures

People seek connection with people.

We are hardwired to seek out other people. That’s why we look at faces in crowds, pause at silhouettes, or follow the gesture of a figure in an image.

In scenic rendering, figures aren’t just placeholders—they’re emotional touchstones. They let the viewer place themselves in the world. They scale the space, yes—but more importantly, they activate it. A single figure looking out a window can do more storytelling than any object on a shelf.

This is what makes a space feel inhabited, even in stillness.

3. Composition Directs the Eye

Just like a director blocks a scene, the designer blocks a frame. Where the eye lands, where it travels next—those are choices.

A strong composition tells the viewer how to look at the world you're creating. It's rhythm, framing, and spatial relationships. Composition isn’t a background element. It’s an invisible script, guiding attention, revealing story, and holding emotion in place.

4. Lighting is the Invisible Narrator

Light is the design element we feel before we process. It tells us time of day, source, temperature—and more importantly, it tells us how to feel about what we’re seeing.

Lighting creates depth, defines form, and focuses attention. A shaft of light can suggest revelation. A shadow can imply danger.

Think of lighting as scenic storytelling in motion, frozen in time.

5. Color Communicates Instantly

Before we read space, we read tone. Warm tones imply safety, nostalgia, or intimacy. Cool tones may suggest isolation, control, or modernity. Highly saturated colors feel heightened, theatrical. Muted colors can suggest realism or restraint.

Your palette does more than decorate—it sets expectations. It’s emotional shorthand. Use it to reinforce genre, story, and atmosphere, not just aesthetics.

6. Focal Points = Visual Priorities

The eye needs a place to land. And once it lands, it needs a reason to stay.

In a scenic rendering, focal points aren’t just about clarity—they’re about intention. Whether it’s a figure under a pool of light, a glowing portal, or a single object in an empty room, your focal point should be where the story concentrates.

Every scenic image should have visual hierarchy. If everything is emphasized, nothing is understood.

7. Atmosphere Breathes Life

Atmosphere is what separates a digital model from a lived-in world. It's not just fog or glow—it's space between things. It's the distance between figure and wall, the bounce of light off a surface, the hint of air in the room.

Atmosphere tells us the world has depth, weight, and movement, even if no one is speaking or walking through it. It gives the image breath.[Image Placeholder]

This rendering for Tomás and the Library Lady uses layered depth and directional light to create mood and realism.

FAQ: Scenic Rendering & Vectorworks

-

For drafting-based workflows, Vectorworks is ideal. It balances precision with visual clarity and integrates well with rendering plugins or visualization platforms like Twinmotion.

-

Story. Your image should evoke something without needing a caption. Mood, tone, and spatial clarity are more important than detail density.

-

Yes—people create context and scale, but more importantly, they create emotional connection.

-

Yes, especially when paired with good lighting setup, textures, and atmospheric effects. It won’t match photorealistic CGI tools in depth, but it's ideal for theatrical clarity and fast adjustments.

-

Absolutely. The best renderings suggest more than they show. Give just enough detail to invite imagination.

Final Thoughts

Scenic rendering is about more than polish—it’s about precision, composition, and emotional weight. A good rendering isn’t trying to show everything. It’s trying to communicate what matters most.

If you’d like to see how these ideas translate into practice, visit the Rendering & Visualization page to explore examples from past projects.

In the next post, I’ll break down how camera angles and field of view inside Vectorworks can shift the storytelling of your renderings—without adding complexity.

As a scenic designer, I've found myself at the crossroads of tradition and innovation. AI tools have burst onto the scene, but Sora stands apart as something uniquely suited to theatrical visualization. Many of my colleagues are understandably cautious—worried that the human touch and collaborative spirit that define our craft might be diluted by automated shortcuts.

I share those concerns. Yet I can't ignore how the landscape is shifting around us. In architectural visualization and commercial production, AI is already becoming standard practice. Detailed 3D modeling that once took days in Cinema 4D or Unreal Engine is increasingly being replaced by faster, AI-driven alternatives—not because they're better, but because they're more economical and efficient.