Scenic Insights

Welcome to Scenic Insights — a curated collection of reflections, case studies, and tutorials from the world of scenic design. Here, I share thoughts on the creative process, documentation techniques, and emerging tools that shape how we design for stage and screen.

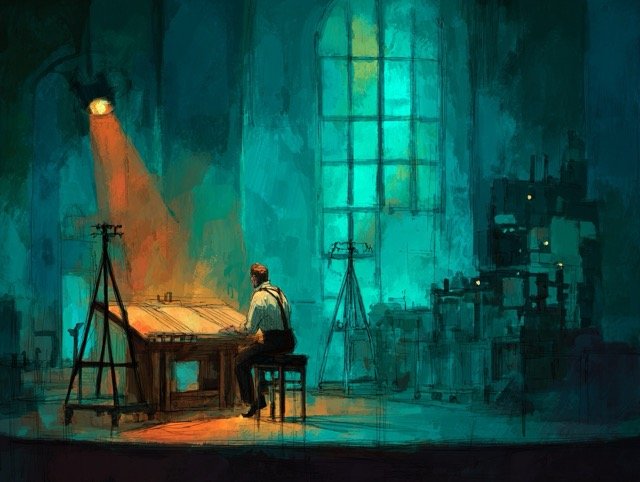

Scenic renderings are more than visual polish—they’re moments of story, frozen in light and space. In this post, I break down what makes a scenic rendering effective, from composition and atmosphere to the emotional weight of lighting and color.

At URTAs, I froze. A designer I admired asked how I’d change an old ground plan—and I blanked. His response stuck with me for years. But that moment taught me something far more valuable than any praise could have: the instinct to re-enter your work.

There's a portrait that watches over the Macklanburg Playhouse. If you've ever performed there, you've seen it—Maude Adams, eyes just over your shoulder as you step into the light. The original Peter Pan. A Broadway icon. But more than that: a pioneer in theatrical lighting and the former head of the drama department at Stephens College.

As a scenic designer, I've found myself at the crossroads of tradition and innovation. AI tools have burst onto the scene, but Sora stands apart as something uniquely suited to theatrical visualization. Many of my colleagues are understandably cautious—worried that the human touch and collaborative spirit that define our craft might be diluted by automated shortcuts.

I share those concerns. Yet I can't ignore how the landscape is shifting around us. In architectural visualization and commercial production, AI is already becoming standard practice. Detailed 3D modeling that once took days in Cinema 4D or Unreal Engine is increasingly being replaced by faster, AI-driven alternatives—not because they're better, but because they're more economical and efficient.

When I first read All My Sons, its themes of family, morality, and the American Dream resonated deeply. It made me think of my father's side of the family, who grew up in the small town of Paris, Missouri. To me, my grandparents embodied that post-war American Dream that Miller explores in his play. My grandfather was a Korean War veteran who built a career as a traveling salesman, driving his blue van through neighboring towns, selling sunglasses, action figures, keychains, and gloves that stocked dime stores across the Midwest. My grandmother, meanwhile, owned and operated a variety store—a quintessential small-town American business built through determination and hard work.

Brandon PT Davis reflects on his evolving identity as a scenic designer, embracing artistic freedom, technology, and creative independence in an industry shaped by metrics and tradition.

Drawing from my years of experience as a professional designer, I've developed a structured approach to craft presentations that simplify the complex narrative of our design process and magnify the impact of our message. I am thrilled to share this methodology with you in this article.

Conceptualization is about delving into the 'What' and the 'Why' of the Design. The research phase lays the foundation by addressing the 'What': identifying the show's needs, the timeline, the setting, and the message to be conveyed. As you transition into the conceptual phase, it's time to delve deeper to unearth the 'Why': the story's significance, the rationale behind the characters' presence, and so on. This phase encapsulates the essence of the narrative and the design vision.

Society often assumes that students are inherently tech-savvy. Memes joke about Millennials teaching their Boomer bosses how to create a PDF. However, the reality is that our Gen Z students are the iPad generation. They're accustomed to mobile software designed for intuitive navigation with a few finger gestures.

Traditional PC software can be overwhelming with its myriad hotkeys and hidden menus. Even software like AutoCAD, which has been around since 1982, relies on a command bar that can seem archaic to digital natives.

From the beginning, it was clear the scenic language needed to support a nonlinear dramaturgy. The play leaps between beach and cathedral, war zone and heaven. Characters slip between time and identity. Puppetry, projections, and movement required the space to transform without literalism.